Though Britain has always been rather half-hearted about the European Union, its membership has been beneficial for all concerned, argues John Peet. It should stay in the club

Oct 17th 2015 | From the print edition

But referendums are by their nature chancy affairs, as a string of previous European examples have shown (see article). Mr Cameron is well aware that the September 2014 referendum on Scottish independence, an issue about which he said he felt far more strongly than he does about the EU, became a closer-run thing than expected. There is no guarantee that the EU referendum will go his way, and if voters chose to leave it would cause great uncertainty not only for business and the economy but for Mr Cameron himself. Assuming that he campaigns for Britain to stay in, which seems a near-certainty, it is hard to see how he could remain prime minister if he lost the vote. Moreover, the Scottish Nationalists have said that if Britain were to withdraw from the EU, they would press for another referendum on Scottish independence, which they might expect to win. So Brexit could, in due course, lead to the break-up of the United Kingdom. The EU referendum will thus become a defining moment not just for Britain's relationship with the rest of Europe but for the future of the country itself.

Special report

- The reluctant European

- Herding cats

- The open sea

- Not what it was

- Common market economics

- Insider dealing

- Alternative lifestyles

- The geopolitical question

One early morsel he threw them was the 2011 European Union Act, which requires any EU-wide treaty that passes substantive new powers to Brussels to be put to a British referendum. That sounded like a big concession, but no new treaties were then in prospect. Another was to launch a wide-ranging review by the British government of the "balance of competences" between the EU and national governments, in hopes that it would favour some shift of powers back from Brussels. Unfortunately for Mr Cameron, the review concluded that the present balance was about right, so the Tories quietly buried it.

Wrong value type supplied for argument vid.

We will do such things…

In 2012 Mr Cameron offered the Eurosceptics another sop: he promised to deliver a big flag-waving speech on Britain and the EU in a continental European city. He eventually gave it at the London headquarters of Bloomberg, an international media group, in January 2013, promising that, if the Tories were re-elected in May 2015, he would renegotiate Britain's membership and hold an in-out referendum by the end of 2017. He later declared that the renegotiation provided a chance to "reform the EU and fundamentally change Britain's relationship with it" and that, to underpin this, he would aim for "full-on treaty change".Yet the reforms that Mr Cameron has since gone on to propose, most recently at an EU meeting of heads of government in June, hardly match this rhetoric of fundamental change. That may be why his government has been coy about setting them out in much detail ahead of the EU summit in December that is meant to agree to them. Still, his proposals can be summarised under six broad headings.

First, migration. Mr Cameron is seeking to put a stop to "welfare tourism" by limiting some benefits for new immigrants. In particular, he wants a four-year ban on benefits, including those paid to people in work, being claimed by migrants who arrive from the rest of the EU. Second, he is looking for a general reduction in EU regulation, and in some cases a repatriation of regulatory powers from Brussels to national capitals. Third, he would like to see a stronger push to complete the single market in such fields as services, digital technology and energy. Fourth, he is demanding some form of opt-out for Britain from the treaties' objective of "ever closer union among the peoples of Europe". Fifth, he is determined to give national parliaments, which he calls the true source of democratic authority in the European project, greater powers to block EU legislation. And finally, he wants a guarantee that an increasingly integrated euro zone will not act against the interests of EU countries that remain outside it.

These demands have been carefully calibrated to ensure they have a chance of success. For example, Europe's recent migration and refugee crisis may have made limiting welfare benefits for migrants more acceptable to public opinion in several other member countries, including Germany. Two recent cases in the European Court of Justice suggest that migrants who have not lived in a country and contributed to its welfare system might be legally stopped from claiming benefits as soon as they arrive. Britain (and maybe others) could impose some minimum length-of-residence requirements that should avoid charges of discrimination against other EU nationals.

In the same vein, the European Commission under Jean-Claude Juncker has already announced plans to cut red tape and unnecessary regulation; indeed, it has withdrawn some 80 draft directives and is considering repealing others already in force. It has also launched new efforts to complete the single market for energy, digital technology and services, and to add a capital-markets union. Even the Netherlands, which has traditionally been in favour of the EU, has said that the era of ever closer union is over, and the European Council conceded in June last year that the phrase could be interpreted in different ways. The Dutch and Scandinavians also want to enhance the role of national parliaments, as does Frans Timmermans, a commission vice-president and former Dutch foreign minister. And the eight other EU countries besides Britain that are not in the euro will also be keen to ensure that the euro zone does not act against their interests.

No EU country and none of the Brussels elite actively want Britain to leave

Even more important, no EU country and none of the Brussels elite actively want Britain to leave. Everybody understands that Brexit would inflict grave damage on the EU (though some reckon that the damage to Britain would be greater still). As one of Europe's most important powers in foreign policy and defence, Britain would be missed. Yet it is also clear that there are limits to the concessions other countries are willing to make to persuade it to stay. And Mr Cameron is well aware that the reforms he is looking for will need the assent not just of the governments of all 27 other EU countries but, in most cases, of the European Parliament as well. Who's for ever closer union?

Who's for ever closer union? Sensibly enough, Mr Cameron has decided not to demand things that he cannot get, such as an end to the free movement of labour, a veto for the House of Commons over all EU laws or a restoration of Britain's opt-out from all social and employment laws. Leaving aside opposition from other countries, he realises that if he insists on big changes to social legislation he might lose the backing of Britain's trade unions and perhaps even of the Labour Party under its new far-left leader, Jeremy Corbyn.

Even so, several of the changes on Mr Cameron's wishlist will be tricky to secure. A recent study by the European Council on Foreign Relations, a think-tank, concluded that two-thirds of Mr Cameron's proposals lacked sufficient support from other member governments to pass. Promises to complete the single market and cut back future regulation are vague enough to be endorsed across the EU, but any British attempts to water down existing rules will be resisted, most strongly by the French and the European Parliament. East European countries will fight restrictions on benefits for migrants within the EU, and even Spain and France are not convinced they are a good idea. Euro-enthusiasts may not want to offer a legally watertight British opt-out from ever closer union, however malleable the phrase may be in practice. And the European Parliament may oppose efforts to give national parliaments greater powers to block EU legislation.

Yet most EU experts in national capitals expect that, perhaps after some stage-managed rows at EU summits in the small hours, it should be possible to agree on a set of reforms that are reasonably close to what Mr Cameron is asking for. And most also believe that this should be enough for him to persuade Britons to vote for remaining in the EU.

1975 and all that

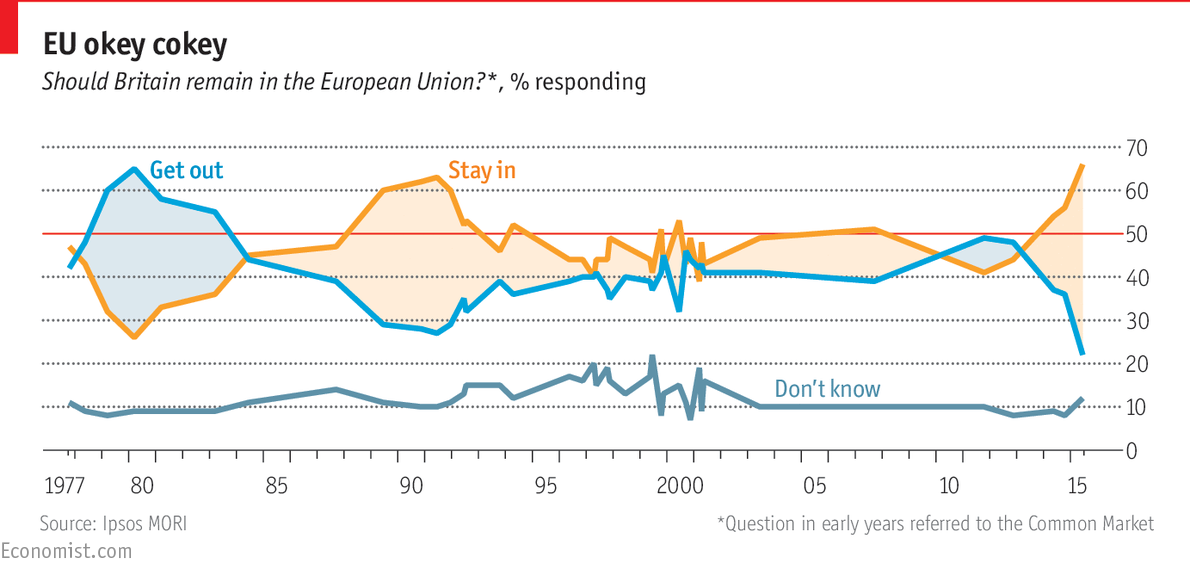

If that sounds optimistic, it is at least based on a clear precedent: the referendum in June 1975, when Britons voted to stay in what was then the European Economic Community (EEC). In effect, Mr Cameron is trying to repeat a trick pulled off by his Labour predecessor at the time, Harold Wilson, though the parties' starting positions have been more or less reversed. In 1974-75 Wilson faced a deep split over EEC membership within his party, whereas the Tories were largely united in favour. Today it is the Tories that are deeply split, whereas most of Labour wants to stay in. Wilson solved his internal party problems by promising a renegotiation of Britain's membership terms, followed by an in-out referendum. He then asked for mostly minor concessions (on the EEC budget he got nothing of any substance, leaving it to Margaret Thatcher to secure a genuine improvement a decade later). Mr Cameron has adopted the same strategy, but is also seeking treaty change. Wilson did not, yet although the changes he secured were widely derided as "cosmetic", he won the 1975 referendum convincingly.Mr Cameron can take comfort not only from this precedent, but also from the fact that he is starting in an apparently stronger position. In early opinion polls after Wilson's 1974-75 renegotiation a majority was in favour of withdrawing from the EEC, yet after a vigorous Yes campaign two-thirds voted to stay. This time round most opinion polls were strongly in favour of remaining in even before Mr Cameron had won the election (see chart), though the lead has decreased sharply in the past few weeks and some recent polls have shown majority support for leaving.

Second, some of Britain's most influential newspapers (the Daily Mail, the Daily Express, the Daily Telegraph, perhaps even the Sun and the Times) may be campaigning to leave this time, whereas in 1975 only the Morning Star advocated withdrawal. In 1975 the government and the In campaign managed to present the Outs as a bunch of woolly extremists. That will be much harder now, for two additional reasons.

One is the relative economic performance of Britain and the rest of Europe. In 1975, as in the early 1960s, when a British government first applied for EEC membership, continental Europe's economies were widely thought to be doing a lot better than Britain's. Indeed, it was the desire to catch up with West Germany and France that lured Britain into joining the club in the first place. Now Britain is generally felt to be well ahead of the rest of the EU, especially the euro zone. The long-drawn-out euro crisis, the recent savage treatment of Greece and the continuing failure of countries like France and Italy to embrace economic reform have done much to strengthen the Out campaign, despite the fact that Britain is not in the single currency.

The second, even more important, issue is immigration, which according to opinion polls is now the biggest concern of British voters. Before the 2010 election, and then again before the 2015 one, Mr Cameron promised to reduce net migration into Britain "from the hundreds of thousands to the tens of thousands". Yet the latest figures, for the year to March 2015, put it at 330,000, a record high. Worse, the largest year-on-year rise was in the numbers of migrants from other EU countries, who now account for roughly half the total. The European crisis over migrants and refugees from Syria in recent months has made things harder for the In campaign, even though Mr Cameron has refused to join an EU-wide scheme to spread the load and has offered to take just 20,000 of them over five years.

Against this background, Mr Cameron's promise merely to set limits on benefits for migrants seems tame. Eurosceptics like Mr Farage have pointed out that it is impossible to control migration from Europe so long as Britain remains in the EU. If the Out campaign can persuade voters that the referendum is not really about the EU but rather about whether they want more or less immigration, it will greatly boost its chances of winning.

The Labour Party's new leader, Mr Corbyn, could also make life harder for Mr Cameron. He is by instinct a Eurosceptic, even if a substantial majority of his party is not. He sees the EU as a capitalist, liberal club that is too fond of austerity, and also as a possible threat to his plans to renationalise the railways and utilities. Although he has said he will campaign to remain in, he is unlikely to do much to help Mr Cameron win his referendum.

Want more? Subscribe to The Economist and get the week's most relevant news and analysis.

eport/21673505-though-britain-has-always-been-rather-half-hearted-about-european-union-its

..

eport/21673505-though-britain-has-always-been-rather-half-hearted-about-european-union-its

..

Brak komentarzy:

Prześlij komentarz